Guest Article by Dr Katerina Palascha, Senior Research Manager, European Food Information Council (EUFIC)

A significant proportion of the global chronic disease burden is caused by dietary patterns that are low in plant-based foods and high in red/processed meat, and foods high in sugar, salt, or unhealthy fats [1]. At the same time these sub-optimal dietary patterns have a detrimental impact on the environment [2]. Consumers with low socioeconomic status (SES) are more likely to have diets that are less healthy and environmentally friendly [3] and worse dietary-related health outcomes [4] as a result of the limited availability of, accessibility to, and affordability of healthy and sustainable food that consumers with low SES often encounter [5].

Yet, there is another important challenge that limits access of socioeconomically disadvantaged consumers to healthy and sustainable eating: inequalities in receiving health information. Low SES is associated with lower access to health information, limited trust in such information, and lower health literacy, and these factors partly explain why low SES consumers tend to have worse diet quality and poorer health [4, 6, 7].

Therefore, making information about healthy and sustainable eating accessible, understandable, and relevant to vulnerable consumers who experience poverty could facilitate their transition to healthier and more sustainable diets, thereby improving human and planetary health. This was the aim of the research that was recently conducted by the European Food Information Council (EUFIC) in collaboration with the social service organisation Caritas Trieste in Italy [8]. EUFIC and Caritas Trieste gave consumers with low SES a voice in order to identify their communication needs and develop tailored communication material about healthy and sustainable eating to help empower them to make the dietary shift.

To do this, they first conducted focus groups with consumers with low SES and professionals of the Caritas organisation to understand the main barriers that consumers face when it comes to healthy and sustainable eating. Main barriers were limited budget for groceries, low availability of fresh products in food banks, lack of cooking skills, misperceptions about products from unknown brands, perceived disconnect between diet and health, limited awareness of/attention to food-related environmental impacts, limited trust in health information, not speaking the local language, and limited motivation to eat healthily and sustainably. To address these barriers, eight infographics about healthy and sustainable eating were developed and were tested via an online survey in a larger sample of Italian residents with low SES (n = 134), including service users of two Caritas social supermarkets (43% of the sample) and migrant consumers (20% of the sample).

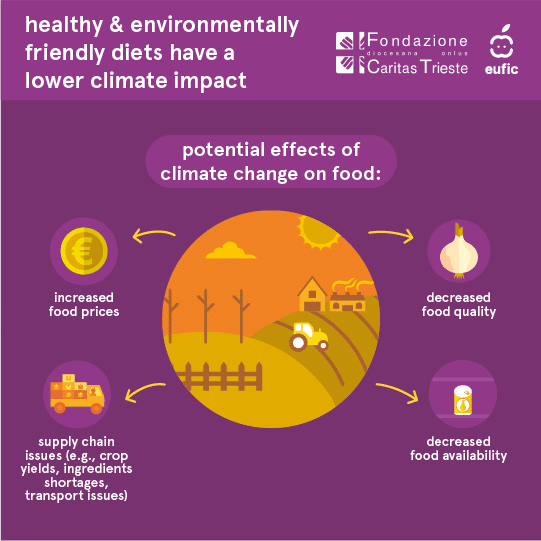

The results were promising. Participants thought that the infographics about healthy and sustainable eating were moderately effective in increasing their motivation, capability, and opportunities for eating more healthily and sustainably. They also found the information moderately useful and likely to impact their behaviour. Moreover, for native consumers certain messages seemed to be more effective than others. For example, natives thought that information about food-related risks of climate change (e.g., reduced food quality, increased food prices), and information about environmental and health benefits of healthy and sustainable eating (e.g., reduced greenhouse emissions, reduced risk of chronic diseases) was more motivating than recommendations on how to eat healthily and sustainably on a budget. They also thought that information about benefits of canned/frozen fruits, vegetables, and pulses (e.g., convenience, affordability) created more opportunities for eating healthily and sustainably compared to information about how food that is branded versus food of a generic brand can have the same nutritional value.

In contrast, migrants showed more indifferent responses to the various infographics and they were generally less motivated to shift towards healthier and more sustainable eating. It was also found that migrants had limited access to and seeking of nutrition-related information and lower trust in sources of nutrition-related information, which might explain the above findings. Finally, in line with previous evidence on the limited affordability and availability of healthy and sustainable food in communities with low SES, this survey found that consumers cut down on sweets and sugar-sweetened beverages but also on important protein sources such as fish, meat, and nuts as a way of coping with their limited budget. The survey/focus groups also revealed that food banks offer a limited availability of fresh fruits and vegetables to their beneficiaries. Therefore, this research acknowledges that although tailor-made messages are promising in increasing motivation, capability, and opportunities for healthy and sustainable eating among consumers with low SES, structural changes around the limited affordability and availability of healthy and sustainable food are also needed to tackle inequalities that affect the most vulnerable consumers.

The results of this research were used to develop a toolkit of recommendations on how to communicate about healthy and sustainable eating to consumers with low SES, while also providing recommendations for changes at the structural level (concerning food policy, food production, education, etc.). This toolkit may be useful for science communicators, researchers, health professionals, journalists, NGOs, policy makers, retailers, and food banks.

References

[1] Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019). Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2020.

[2] Willett, W., Rockström, J., Loken, B., Springmann, M., Lang, T., Vermeulen, S., … & Murray, C. J. L. (2019). Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet, 393(10170), 447–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31788-4

[3] Darmon, N., & Drewnowski, A. (2015). Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: a systematic review and analysis. Nutrition reviews, 73(10), 643–660. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuv027

[4] Stormacq, C., van den Broucke, S., & Wosinski, J. (2019). Does health literacy mediate the relationship between socioeconomic status and health disparities? Integrative review. Health Promotion International, 34(5), E1–E17. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day062

[5] Fanzo, J., & Davis, C. (2019). Can Diets Be Healthy, Sustainable, and Equitable?. Current obesity reports, 8(4), 495–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-019-00362-0

[6] Ishikawa, Y., Nishiuchi, H., Hayashi, H., & Viswanath, K. (2012). Socioeconomic status and health communication inequalities in Japan: a nationwide cross-sectional survey. PloS one, 7(7), e40664. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0040664

[7] Vaudin, A., Wambogo, E., Moshfegh, A., & Sahyoun, N. R. (2021). Awareness and use of nutrition information predict measured and self-rated diet quality of older adults in the USA. Public Health Nutrition, 24(7), 1687–1697. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020004681

[8] Palascha, A., & Chang, B. P. I. (2024). Which messages about healthy and sustainable eating resonate best with consumers with low socio-economic status?. Appetite, 198, 107350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2024.107350

Disclaimer: the opinions – including possible policy recommendations – expressed in the article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of EPHA. The mere appearance of the articles on the EPHA website does not mean an endorsement by EPHA.